The New Denial of Imperialism on the Left

It is a sign of the depth of the structural crisis of capital in our time that not since the onset of the First World War and the dissolution of the Second International—during which nearly all of the European social democratic parties joined the interimperialist war on the side of their respective nation-states—has the split on imperialism on the left taken on such serious dimensions.

by

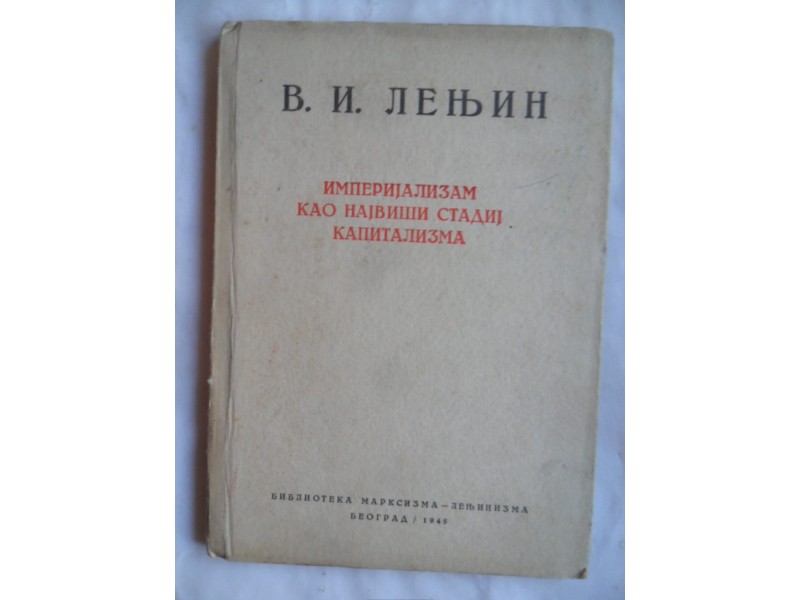

Although the more Eurocentric sections of Western Marxism have long sought to attenuate the theory of imperialism in various ways, V. I. Lenin's classic work Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (written in January–June 1916) has nonetheless retained its core position within all discussions of imperialism for over a century, due not only to its accuracy in accounting for the First and Second World Wars, but also to its usefulness in explaining the post-Second World War imperial order.2 Far from standing alone, however, Lenin's overall analysis has been supplemented and updated at various times by dependency theory, the theory of unequal exchange, world-systems theory, and global value chain analysis, taking into account new historical developments. Through all of this, there has been a basic unity to Marxist imperialism theory, informing global revolutionary struggles.

However, today this Marxist theory of imperialism is commonly being rejected in large part, if not in its entirety, by self-proclaimed socialists in the West with a Eurocentric bias. Hence, the gap between the views of imperialism held by the Western left and those of revolutionary movements in the Global South is wider than at any time in the last century. The historical foundations of this split lie in declining U.S. hegemony and the relative weakening of the entire imperialist world order centered on the triad of the United States, Europe, and Japan, faced with the economic rise of former colonies and semicolonies in the Global South. The waning of U.S. hegemony has been coupled with the attempt of the United States/NATO since the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 to create a unipolar world order dominated by Washington. In this extreme polarized context many on the left now deny the economic exploitation of the periphery by the core imperialist countries. Moreover, this has been accompanied more recently by sharp attacks on the anti-imperialist left.

Thus, we are now commonly confronted with such contradictory propositions, emanating from the Western left, as: (1) one nation cannot exploit another; (2) there is no such thing as monopoly capitalism as the economic basis of imperialism; (3) imperialist rivalry and exploitation between nations has been displaced by global class struggles within a fully globalized transnational capitalism; (4) all great powers today are capitalist nations engaged in interimperialist struggle; (5) imperialist nations can be judged primarily on a democratic-authoritarian spectrum, so that not all imperialisms are created equal; (6) imperialism is simply a political policy of aggression of one state against another; (7) humanitarian imperialism designed to protect human rights is justified; (8) the dominant classes in the Global South are no longer anti-imperialist and are either transnationalist or subimperialist in orientation; (9) the "anti-imperialist left" is "Manichean" in its support of the morally "good" Global South against the morally "bad" Global North; (10) economic imperialism has now been "reversed" with the Global East/South now exploiting the Global West/North; (11) China and the United States head rival imperialist blocs; and (12) Lenin was mainly a theorist of interimperialism, not of the imperialism of center and periphery.3

In order to understand the complex theoretical and historical issues involved here, it is important to go back to Lenin's analysis of imperialism, conceiving it not simply in terms of Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, but in relation to his whole set of writings on imperialism from 1916–1920. It will then be possible to perceive how the theory of the imperialist world system developed over the last century on the basis of Lenin's analysis and the early Communist International (Comintern), followed by further theoretical refinements after the Second World War in the work of the main theorists of dependency, unequal exchange, the capitalist world-system, and global value chains. This history will set the stage on which to critique the current denial of imperialism on much of the left.

Lenin's Overall Theory of Imperialism

It is an indication of the enormous power of Lenin's analysis in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism that those left thinkers contending that imperialism has been transcended nevertheless refer back to Lenin's classic work. Hence, it is commonly argued today by the Eurocentric left that Lenin did not focus on issues of inequality between colonizing and colonized countries or between center and periphery. Rather, we are told that he saw his work as mainly concerned with horizontal conflict between the great capitalist powers.4 Thus, William I. Robinson, a distinguished professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and a member of the executive board of the Global Studies Association of North America (GSA), goes so far as to insist that Lenin's theory of imperialism had nothing to do with the exploitation of one nation by another.

The idea predominant among leftists is that Lenin advanced a nation-state or territorially-based theory of imperialism. This is fundamentally wrong. He advanced a class-based theory. A nation cannot exploit another nation—that is just absurd reification. Imperialism has always been a violent class relation, not between countries but between global capital and global labour.… Most on the left see the exploiter as an "imperialist nation." This is a reification insofar as nations are not and have never been macro-agents. A nation cannot exploit or be exploited.5

However, far from the exploitation of one nation by another being fundamentally opposed to Marxism, Karl Marx exhibited nothing but scorn for those that he said could not see "how one nation can grow rich at the expense of another."6 Similarly, Lenin explicitly contended in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism that the dominant tendency of imperialism was "the exploitation of an increasing number of small or weak nations by an extremely small group of the richest and most powerful nations." Later, he stated that "the exploitation of oppressed nations…and especially the exploitation of colonies by a handful of Great Powers" was the economic taproot of imperialism. Lenin made it absolutely clear that to refer to exploitation in this context meant that an imperialist nation at the center of the capitalist world system "draws surplus-profits from" an oppressed nation in the colonial/semicolonial/dependent world.7

Still, according to Vivek Chibber, professor of sociology at New York University and editor of Catalyst, Lenin's whole conception of economic imperialism as monopoly capitalism was "flawed," as were Lenin's notions that imperialism was economic (and not simply political), and that there was an upper stratum of the working class (the labor aristocracy) in the wealthy capitalist countries that benefited from imperialism. In all of these ways, Chibber has suggested, Lenin's analysis was in error, while the significance of his theory was mainly confined to the realm of intercapitalist competition.8

Such grave misconceptions with respect to Lenin's theory and its contemporary relevance are traceable in part to a tendency of radical academics in the West to study his Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism in abstraction from his other major writings on imperialism. These include six key pieces, written between 1916–1920: "The Socialist Revolution and the Rights of Nations to Self-Determination (Theses)" (written in January–February 1916); "Imperialism and the Split in Socialism" (written in October 1916); "Address to the Second All-Russia Congress of Communist Organizations of the Peoples of the East" (November 1919); "Preliminary Draft Theses on the National and Colonial Questions" (for the Second Congress of the Communist International [June 1920]); "Preface to the French and German Editions" of his book on imperialism (July 6, 1920); and "The Report of the Commission on the National and Colonial Questions" (July 26, 1920).9 These additional, mostly later, writings by Lenin on the national and colonial questions supplement Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, focusing directly on the issue of the exploitation of underdeveloped countries by the major imperialist powers, primarily the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan (which today, with the addition of Canada, make up the Group of Seven, or G7).10

"If it were necessary to give the briefest possible definition of imperialism," Lenin wrote in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, "we should have to say imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism." The rise of monopolistic accumulation had supplanted the era of free competition, creating a sphere of enormous surplus profits in relatively few corporations, which came to dominate the economy.11 In the five characteristics of imperialism that Lenin listed right after this, he emphasized the concentration and centralization of capital on a national and world scale as the primary characteristic of imperialism. The second characteristic was the merging of industrial and banking capital to form financial capital and a financial oligarchy. The third was the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities, that is, the shift of capital to a global field of operation. The fourth, summing up the previous three, was the domination of the world by a relatively small number of international capitalist monopolies. The fifth was the completion of "the territorial division of the world among the great capitalist powers."12

Lenin's analysis was strongly opposed to that of Karl Kautsky, the main theorist of the German Social Democratic Party, who had argued that imperialism would develop into an "ultra-imperialism," in which the leading capitalist countries unified through a "federation of the strongest," a thesis that was to be disproven by the First and Second World Wars. Although the main capitalist states did provide a more collective imperialist front after the Second World War, it was the result of the global hegemony of the United States, which reduced the other leading capitalist states to the status of junior partners. Overall, Kautsky's view of imperialism as a policy has been shown to be immeasurably weaker than Lenin's view of it as a system.13

As the Research Unit for Political Economy (RUPE, India) has noted, "the focus of Lenin's Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism was on uncovering the character of the [First] world war and its roots in capitalism itself; thus he did not explore in that particular work the impact of imperialism on colonies and semi-colonies."14 To arrive at that part of his analysis, it is necessary to look at Lenin's other, mostly later, writings on imperialism at a time when he was directly confronted with the anti-imperialist struggle in the nations of the periphery, particularly in Asia, in the context of the formation of the Comintern. Following the October Revolution, Soviet Russia was immediately confronted with the military interventions of the imperial powers on the side of the White forces in the Russian Civil War. Winston Churchill, Lenin observed, cheerfully proclaimed that Russia was being invaded in "a campaign of fourteen nations," primarily the great imperial powers of the United States, Britain, France, Italy, and Japan, who were united in their opposition to the October Revolution.15 At the same time, the Russian Revolution inspired major insurgencies in Asia, as in China's May Fourth movement (1919), the anti-Rowlatt Act agitation in India (1919), and the Great Iraqi Revolution (1920).16

Lenin, of course, was too adept a political thinker to fail to recognize the implications of these new revolutionary movements. He therefore focused even more on the exploitation of the underdeveloped economies, which had always been the primary historical contradiction underlying his analysis of imperialism as a whole. The exploitation of colonies, semicolonies, and dependencies by the imperial powers was already visible in Lenin's writings in 1916. In "The Socialist Revolution and the Rights of Nations to Self-Determination," he argued that a degree of self-determination was possible for some colonized/dependent nations under capitalism, but only if revolutions brought it about. Such revolutions on the outskirts of the system ultimately demanded revolutions in the metropoles. "No nation," he wrote, referring to an earlier statement by Marx, "can be free if it oppresses other nations."17

In "Imperialism and the Split in Socialism," Lenin stated:

A handful of wealthy countries—there are only four of them, if we mean independent, really gigantic, "modern" wealth: England, France, the United States and Germany—have developed monopoly to vast proportions, they obtain superprofits running into hundreds, if not thousands, of millions, they "ride on the backs" of hundreds and hundreds of millions of people in other countries and fight among themselves for the division of the particularly rich, particularly fat and particularly easy spoils. This [exploitation and the spoils it delivers], in fact, is the economic and political essence of imperialism.18

Lenin not only argued that monopoly capital exploited colonies, semicolonies, and dependencies, obtaining by these means superprofits, but that this, as Frederick Engels had intimated, allowed it to "bribe" a narrow section of the working class (the upper stratum of labor), a proposition known as the labor aristocracy thesis.19 He was to reiterate this emphatically in his 1920 preface to Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.20 It was this, he argued, that explained the more conservative nature of the British working-class movement, as well as that of all core imperialist countries. The answer here, "if we wish to remain socialists," he wrote, is "to go down lower and deeper," below the narrow upper stratum of the working class, "to the real masses; this is the whole meaning and the whole purport of the struggle against [the] opportunism" of the labor aristocracy and social democracy.21

In his "Address to the Second All-Russia Congress of the Communist Organizations of the Peoples of the East," Lenin underscored how an "insignificant section of the world's population" had given itself "the right to exploit the majority of the population of the globe." Under these circumstances, the struggle against imperialism even took priority over the class struggle, though they remained intrinsically connected. "The socialist revolution will not be solely, or chiefly, a struggle of the revolutionary proletarians in each country against their bourgeoisie—no, it will be a struggle of all imperialist-oppressed colonies and countries, of all dependent countries, against international imperialism…. The civil war of the working people against the imperialists and exploiters in all the advanced countries is beginning to be combined with national wars against international imperialism."22

Lenin advanced this position further in the "Preliminary Draft Theses on the National and Colonial Questions." He drew a sharp distinction between the "oppressed, dependent and subject nations" and "the oppressing, exploiting and sovereign nations." Here he made it clear that "proletarian internationalism demands…that the interests of the proletarian struggle in any one country be subordinated to the struggle on a world-wide scale." Capitalism, he argued, often sought to disguise the level of international exploitation through its creation of states that were nominally sovereign, but which were actually dependent on the imperial countries "economically, financially, and militarily."23

Lenin's "Report of the Commission on the National and Colonial Questions" reiterated these points and concluded that under current conditions of underdevelopment in the oppressed nations, "any national movement, can only be a bourgeois-democratic movement." These "national-revolutionary" struggles, despite their predominant class character, needed to be supported, but only as long as these were "genuinely revolutionary" struggles. He strongly rejected the view that such revolutions "must inevitably go through the capitalist stage," arguing rather that they could, given their anti-imperialist and complex class composition, and with the example of the Soviet Union before them, conceivably develop into genuine movements toward socialism that would achieve many of the tasks of development associated with capitalism on noncapitalist terms.24

Lenin's "Preliminary Draft Theses on the National and Colonial Questions," when presented to the Second Congress of the Comintern, were followed, with Lenin's support, by "Supplementary Theses on the National and Colonial Question," written by the Indian Marxist M. N. Roy, which were adopted along with Lenin's "Preliminary Draft Theses." Key to these "Supplementary Theses" was the explicit statement that imperialism had distorted economic development in the colonies, semicolonies, and dependencies. Colonies like India had been deindustrialized, blocking their progress. Superprofits had been extracted from economically "backward countries" and colonies by the imperial powers:

Foreign domination constantly obstructs the free development of social life; therefore the revolution's first step must be the removal of this foreign domination. The struggle to overthrow foreign domination in the colonies does not therefore mean underwriting the national aims of the national bourgeoisie but much rather smoothing the path to liberation for the proletariat of the colonies…. The real strength, the foundation of the liberation movement, will not allow itself to be forced into the narrow framework of bourgeois-democratic nationalism in the colonies. In the greater part of the colonies there already exist organised revolutionary parties which work in close contact with the working masses.25

Two years later, in the "Theses on the Eastern Question" of the Fourth Congress of the Comintern in 1922, some of the core notions associated with dependency theory were introduced:

It is this [post-First World War] weakening of imperialist pressure in the colonies, together with the steadily growing rivalry between the different imperialist groupings, that has facilitated the development of indigenous capitalism in the colonial and semicolonial countries, which has expanded and continues to expand beyond the narrow and restrictive limits of imperialist rule by the great powers. Previously, great-power capitalism sought to isolate the backward countries from world economic trade, in order in this way to secure its monopoly status and achieve super-profits from the commercial, industrial, and fiscal exploitation of these countries. The rise of indigenous productive forces in the colonies stands in irreconcilable contradiction to the interests of world imperialism, whose very essence is to take advantage of the variation in the level of development of productive forces in different arenas of the world economy to achieve monopoly super-profits.26

The "Theses on the Revolutionary Movement in the Colonies and Semi-Colonies" in the Comintern's Sixth Congress, in 1928, represented a high point in imperialism theory in the interwar period. There, it was stated that "The entire economic policy of imperialism in relation to the colonies is determined by its endeavour to preserve and increase their dependence, to deepen their exploitation and, as far as possible, to impede their independent development…. The greater portion of the surplus value extorted from…cheap labour power" in the colonies and semicolonies is exported abroad, resulting in a "bleeding of the national wealth of the colonial countries."27

The most difficult theoretical and practical problem was the class basis of anti-imperialist revolution in the underdeveloped countries. Lenin had emphasized that the revolt against imperialism would have to carry out the developmental objectives usually associated with the national bourgeoisie, but that the nature of the "national revolutionary" struggle would not necessarily be determined by the national bourgeoisie. Mao Zedong was to make an important contribution to the anti-imperialist struggle and socialist revolution in his "Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society" in 1926. Here Mao argued that the big, monopoly-capitalist bourgeoisie, together with the landlord class, constituted a comprador class-formation that served as an appendage of international capital. The smaller national bourgeoisie, meanwhile, was too weak, and mainly sought to turn itself into a big bourgeoisie. The revolutionary forces thus depended on the petty bourgeoisie, the semi-proletariat, the proletariat, and, ultimately, the peasants.28

All of these and most subsequent developments in the theory of imperialism had their roots in Lenin. As Prabhat Patnaik wrote,

The significance of Lenin's Imperialism lay in the fact that it totally revolutionised the perception of the revolution. Marx and Engels had already visualised the possibility of colonial and dependent countries having revolutions of their own even before the proletarian revolution in the metropolis, but these two sets of revolutions were seen to be disjoint; and both the trajectory of the revolution in the periphery and its relation to the socialist revolution in the metropolis remained unclear. Lenin's Imperialism not only linked the two sets of revolutions, but also made the revolution in the peripheral countries a part of the process of mankind's moving towards socialism. It therefore saw the revolutionary process as an integrated whole.29

Dependency, Unequal Exchange, the Imperialist World System, and Global Value Chains

After the Second World War, the imperialist world system had historically evolved beyond the geopolitical conditions in Lenin's time. The United States was now the unquestioned hegemonic power in the capitalist world system and immediately launched a Cold War dedicated to "containing" the Soviet Union while repressing revolution everywhere in the world. A revolutionary decolonizing wave, much of it inspired by Marxism, nonetheless swept Asia and Africa following the triumph of the Chinese Revolution in May 1949.

In contrast to Asia and Africa, South and Central America included relatively few official colonies, due to their nineteenth-century anticolonial revolts against Spain and Portugal, leading to the formation of sovereign states. Nevertheless, Latin American states had long been reduced to economic dependencies or neocolonies, first of Britain and then the United States. Hence, the main issue in the region was overcoming the economic, political, and cultural dependency imposed by U.S. imperialism. Latin American Marxist theory, particularly with respect to imperialism, can be said to have had its roots in the work of the Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui, who wrote in 1929, "We are anti-imperialists because we are Marxists, because we are revolutionaries, because we oppose capitalism with socialism…and because in our struggle against foreign imperialism we are fulfilling our duty of solidarity with the revolutionary masses of Europe."30 At the time Mariátegui was writing, Augusto César Sandino's struggle against U.S. intervention in Nicaragua was awakening anti-imperialist consciousness across Latin America. Later, the victory of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, inspired by the anti-imperialism of José Martí, and evolving into a struggle for socialism, brought revolution against imperialism to the fore once again in Latin America, which joined Asia and Africa in this respect.31

Due to the revolutionary wave on all three continents of the third world in the early decades of the post-Second World War period, Lenin's original analysis of imperialism was deepened and broadened, developing into a rich global tradition reflecting many different historical conditions and vernaculars—but always pointing to the need for revolutionary struggle.

A major figure in the development of both imperialism theory and dependency theory after the Second World War was Paul A. Baran, author of The Political Economy of Growth (1957).32 Baran was born in Nikolaev, Ukraine, in the Tsarist Russian Empire in 1910. He studied economics at the Plekhanov Institute of Economics in the Soviet Union and at the University of Berlin, also working as economic assistant to Friedrich Pollock at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt. Later he emigrated to the United States and studied economics at Harvard University during the Keynesian Revolution. During the Second World War and in the immediate aftermath, he worked with the Strategic Bombing Survey in Germany and Japan. After the war, he worked for the Federal Reserve Board and then obtained a tenured position as professor of economics at Stanford University. Prior to the publication of The Political Economy of Growth, Baran presented a series of lectures at Oxford University, where much of the book was prepared, and was employed by the Indian Statistical Institute in Calcutta.33 He was a strong supporter of the Cuban Revolution and exercised an important influence on Che Guevara. In 1966, Baran and Paul M. Sweezy wrote Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Social and Economic Order.34

Reflecting this extremely broad background, Baran embodied in his work not only the imperialism theories of Lenin, the Comintern, and Mao, but also the experiences of Soviet and Indian economic planning. At the same time, he integrated this with the new conditions of the post-Second World War period. He was well-placed therefore to emerge as a foundational thinker in Marxian dependency theory. He argued that imperialism had "immeasurably distorted" and blocked development throughout the underdeveloped world.35 In 1830, the countries in what was to be called the "third world" accounted for 60.9 percent of the world's industrial potential. By 1953, this had dropped to 6.5 percent.36 Introducing his concept of economic surplus (in its simplest form, "the difference between society's actual current output and its actual current consumption"), Baran explained that the root problem preventing development in the underdeveloped countries was the siphoning off of the surplus by the major imperialist powers, which then invested the appropriated surplus either in their own economies, or else in the periphery in such a way as to enhance their long-term exploitation of the underdeveloped countries.37 As with Engels and Lenin, Baran argued that an upper layer of workers in the countries of the imperial center indirectly benefited from imperialism, and thus formed a "'labor aristocracy' gathering the crumbs from the monopolistic table," at odds with the bulk of the working class.38

An important component of Baran's dependency theory was the comparison of Japan with India. Japan represented a singular instance of economic development outside of Europe or European white-settler colonies. The imperialist powers had concentrated their efforts in East Asia in the nineteenth century mainly on subjugating China, and had thus failed to colonize Japan. With the Meiji Restoration in 1868, which took place in response to growing military threats and the nascent imposition of unequal treaties by the West, Japan was able to create the internal social basis for rapid industrialization, facilitated by the appropriation of Western technological knowhow. By 1905, Japan's entry to great power status was signaled by its victory in the Russo-Japanese War. In contrast, India, which had been colonized by the British in the eighteenth century, saw its industry destroyed by the British and was placed in a permanent state of underdevelopment or dependent development.39

Following Mao, Baran insisted that a comprador class or big bourgeoisie (allied with the large landlords) in the underdeveloped countries was linked directly to international capital and played a parasitic role in relation to their own societies.40 "The main task of imperialism in our time," he wrote, was "to prevent, or, if that is impossible, to slow down and control the economic development of underdeveloped countries." He explained that, "While there have been vast differences among underdeveloped countries," in this respect, "the underdeveloped world as a whole has continually shipped a large part of its economic surplus to more advanced countries on account of interest and dividends. The worst of it is, however, that it is very difficult to say what has been the greater evil as far as the economic development of underdeveloped countries is concerned: the removal of their economic surplus by foreign capital or its reinvestment by foreign enterprise."41 In nearly all respects, the dependent economy was a mere "appendage to the 'internal market' of Western capitalism."42 The only recourse, then, was revolution against imperialism and the setting up of a socialist planned economy. Here Baran pointed to the example of China, which, in dropping "out of the orbit of world capitalism," had become a source of "encouragement and inspiration to all other colonial and dependent countries."43

The Political Economy of Growth was published only two years after the 1955 Bandung Conference, which launched the Nonaligned Movement of third-world states, and proved enormously influential.44 Although Latin American countries were not part of the Bandung Conference, the new Third World perspective helped engender an explosion of work in Marxism and radical dependency analysis in Latin America, which was inspired much more concretely by the Cuban Revolution. Baran visited Cuba in 1960, along with Leo Huberman and Sweezy, and met Che, who was then president of the National Bank. Che associated himself closely with Baran's general analysis of underdevelopment. As Che was to declare in 1965, "Ever since monopoly capital took over the world, it has kept the greater part of humanity in poverty, dividing all the profits among the group of the most powerful countries."45 Some of the leading contributors to dependency analysis in Latin America and the Caribbean included Vânia Bambirra, Theotônio Dos Santos, Rodolfo Stavenhagen, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Pablo González Casanova, Ruy Mauro Marini, Walter Rodney (whose best-known work focused on the underdevelopment of Africa), Clive Thomas, and Eduardo Galeano.46 German-American economist Andre Gunder Frank also had a deep impact beginning with the publication in 1967 of his Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, which highlighted "the development of underdevelopment."47

In Africa, Samir Amin, a young Egyptian-French Marxist economist, introduced a full-scale critique of mainstream development analysis in his 1957 doctoral dissertation (completed at age 26 in the same year as Baran's book was published), which was later published under the title Accumulation on a World Scale. He subsequently contributed massively to dependency, unequal exchange, and world-systems theory. Much of Amin's analysis focused on the distinction between, on the one hand, "autocentric" economies at the center of the world capitalist system, geared to their own internal logics and expanded reproduction, and, on the other, the "disarticulated" economies of the periphery, where production was structured in terms of the needs of the imperial economies. The disarticulated nature of peripheral economies under imperialism left a revolutionary "delinking" from the logic of the world imperialist order as the only real alternative. For Amin, however, delinking was not about some absolute separation from the world economy or "autarkic withdrawal." Rather, it meant delinking from the world labor-value system organized around a dominant center and dominated periphery, and the transition to a more "polycentric" world.48

A key contribution to imperialism theory was Greek Marxist economist Arghiri Emmanuel's Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade (1969).49 Arguing that in the era of neocolonialism the relation between core countries and those in the periphery was one of inequality in exchange such that one country obtained more labor-value than another, due to the global mobility of capital coupled with the global immobility of labor, Emmanuel's work set off a long debate. This was essentially settled by Amin with his proposition that unequal exchange existed when the difference in wages between Global North and Global South was greater than the difference in their productivities. He went on to argue that the law of value now operated on a world level under globalized monopoly-finance capital.50

The ruling-class reality in the underdeveloped world, according to Amin, was one of "compradorization and transnationalization," requiring new anti-imperialist revolutionary strategies, since there was no longer a national bourgeoisie as such. A revolutionary delinking strategy under these circumstances would depend on "building an anti-comprador social bloc" with the aim of enabling a sovereign project, divorced from the control of the imperialist world-system. With respect to imperialism and class in the advanced capitalist states, Amin suggested that Lenin's labor aristocracy theory did not go far enough to address how the whole "unequal international division of labor" created broad structures supportive of imperialism within the core imperialist states that could not just be wished away. Here what was needed was the "building of an anti-monopoly bloc."51

Much of Marxist dependency theory, beginning in the 1970s, merged into world-system (later world-systems) theory, as pioneered by Oliver Cox, Immanuel Wallerstein, Frank, Amin, and Giovanni Arrighi.52 World-system theory overcame some of the limitations of dependency theory by conceiving of nation-states as part of a capitalist world-system. The world-system thus became the main unit of analysis, seen as divided into centers and peripheries (while also providing for semiperipheries and external areas). However, in some versions of world-system theory, notably the work of Arrighi, there was a divergence from the theory of imperialism, reducing international political-economic relations simply to shifting hegemonies, in line with mainstream international political economy.53

Already in the 1960s, radical political economists had come to center on the critique of multinational corporations, viewed as the global form assumed by monopoly capital, and thus the main transmission belts of economic imperialism. Here, the pioneering analysis emanated from Stephen Hymer, who wrote his breakthrough dissertation in 1960 on The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Direct Foreign Investment, providing a theory of "multinational corporations," based on industrial organization and monopoly theory, in the very year that the term first appeared. This was followed by treatment of the role of multinational corporations and imperialism in Baran and Sweezy's Monopoly Capital and in Harry Magdoff and Sweezy's "Notes on the Multinational Corporation" (1969). The world trajectory of such corporations became central to the whole theory of imperialism as in Magdoff's The Age of Imperialism: The Economics of U.S. Foreign Policy (1969).54

In the 1970s and '80s, much of the evolving research on imperialism shifted from the realm of political economy to that of culture. In line with Joseph Needham's earlier criticism of "Europocentrism" in the 1960s, Amin in 1989 introduced his very influential critique of Eurocentrism, while Edward Said produced his Orientalism (1978) and his Culture and Imperialism (1993).55 With the rise of ecosocialism, the critique of imperialism was also extended to the question of ecological imperialism.56

In the twenty-first century, most analysis of economic imperialism has focused on the global labor arbitrage and global value chains. Never before has the extraction of surplus by the Global North from the Global South been demonstrated so thoroughly in empirical studies. This derives from the fact that international exploitation is now more systematic than ever before: ingrained in the value chains of the global system and embodied in the export of manufactured goods from periphery to semiperiphery to the center.57 The result has been the growing prominence of theories of "superexploitation" (that is, levels of exploitation in the Global South exceeding the global average and undermining the essential subsistence needs of Southern workers) as developed in the work of thinkers such as Marini, Amin, John Smith, and Intan Suwandi.58

Today, we know from the research of Jason Hickel and his colleagues that in 2021 the Global North was able to extract from the Global South 826 billion hours in net appropriated labor. This represents $18.4 trillion measured in Northern wages. Behind this lies the fact that workers in the Global South receive 87–95 percent lower wages for equivalent work at the same skill levels. The same study concluded that the wage gap between the Global North and the Global South was increasing, with wages in the North rising eleven times more than wages in the South between 1995 and 2021.59 This research into the contemporary global labor arbitrage is coupled with recent historical work by Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik that has now documented the astronomical drain of wealth during the period of British colonialism in India. The estimated value of this drain over the period of 1765–1900, cumulated up to 1947 (in 1947 prices) at 5 percent interest, was $1.925 trillion; cumulated up to 2020, it amounts to $64.82 trillion.60

It should be emphasized that the Global North's contemporary drain of economic surplus from the Global South, via the unequal exchange of labor embodied in exports from the latter, is in addition to the normal net flow of capital from developing to developed countries recorded in national accounts. This includes the balance on merchandise trade (import and exports), net payments to foreign investors and banks, payments for freight and insurance, and a wide array of other payments made to foreign capital such as for royalties and patents. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the net financial resource transfers from developing countries to developed countries in 2017 alone amounted to $496 billion. In neoclassical economics, this is known as the paradox of the reverse flow of capital, or of capital flowing uphill, which it ineffectively tries to explain away by various contingent factors, rather than acknowledging the reality of economic imperialism.61

With respect to the geopolitical dimension of imperialism, the focus this century has been on the continuing decline of U.S. hegemony. Analysis has concentrated on the attempts of Washington, since 1991, backed by London, Berlin, Paris, and Tokyo, to reverse this. The goal is to establish the triad of the United States, Europe, and Japan—with Washington preeminent—as the unipolar global power through a more "naked imperialism." This counterrevolutionary dynamic eventually led to the present New Cold War.62

Yet, despite all of the developments in imperialism theory over the last century, it is not the theory of imperialism so much as the actual intensification of the Global North's exploitation of the Global South, coupled with the resistance of the latter, that has stood out. As Sweezy argued in Modern Capitalism and Other Essays in 1972, the sharp point of proletarian resistance decisively shifted in the twentieth century from the Global North to the Global South.63 Nearly all revolutions since 1917 have taken place in the periphery of the world capitalist system and have been revolutions against imperialism. The vast majority of these revolutions have occurred under the auspices of Marxism. All have been subjected to counterrevolutionary actions by the great imperial powers. The United States alone has intervened militarily abroad hundreds of times since the Second World War, primarily in the Global South, resulting in the deaths of millions.64 In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the primary contradictions of capitalism have been those of imperialism and class.

The Growing Denial of Imperialism on the Left

Denial of the reality of imperialism in full or in part has a long history in the Western Eurocentric left beginning with the outright "social imperialism" of the Fabian Society in Britain, and reflected in the social chauvinism of all of the main European social democratic parties at the time of the First World War. However, with the resurgence of the Western left in the post-Second World War period, particularly in the 1960s and '70s, Western socialists adopted a strongly anti-imperialist stance, backing national liberation struggles around the world. This began to fade with the waning of the anti-Vietnam War movement in the early 1970s.65

In 1973, Bill Warren introduced in New Left Review the notion that Marx in the "The Future Results of the British Rule in India" (1853) had seen imperialism as a progressive force, a view that, Warren declared, was later mistakenly reversed by Lenin.66 Warren's interpretation of Marx here was at odds with the much more thoroughgoing treatment by theorists in the United States, India, and Japan from the 1960s on, who demonstrated that Marx, beginning in the early 1860s, had recognized the way in which colonialism blocked development in the colonies.67 Nevertheless, the notion that Marx, and even Lenin, had adopted the view of Imperialism [as the] Pioneer of Capitalism—the title/subtitle of Warren's book published posthumously in 1980—became a commonly accepted postulate on the left.68

Underlying this analysis was the rejection by the Eurocentric left of the conclusion that countries of the capitalist core exploited those of the periphery, through higher rates of exploitation of workers in dependent countries, and the resulting appropriation of a large part of this enormous surplus by the imperialist countries at the center of the system. It has long been argued by Eurocentric socialists—going against the analysis of figures like Lenin, Baran, and Amin—that a higher rate of productivity in the Global North canceled out the wage differential between North and South to the point that the level of exploitation in the North was actually higher than in the South.69 However, this thesis of a higher rate of exploitation in the North has now been definitively disproven as a result of empirical research into unit labor costs and the value captured by the center from labor in the periphery (and semiperiphery) through unequal exchange. Study after study has shown that even when accounting for productivity/skill levels, which are now comparable in export manufacturing in the Global South and in the Global North (since the very same technology, introduced by multinational corporations, is utilized), the rate of exploitation is much higher in the Global South, with its much lower unit labor costs. Indeed, the current trend toward the outright denial of imperialism theory can be attributed in part to an attempt in the face of this growing evidence to avoid the reality of the center's superexploitation of the periphery by abandoning the whole question of imperialism.

At the root of the criticisms of economic imperialism emanating from Western Eurocentric circles has been the rejection of Engels's and Lenin's labor aristocracy thesis. Thus, the whole notion that a section of the working class in the imperialist core of the global economy benefits from imperialism was generally placed out of bounds as politically objectionable. Yet, the existence of a labor aristocracy at some level is difficult to deny on any realistic basis. An indication of this is that study after study has confirmed that the AFL-CIO union leadership in the United States historically has been oriented to business unionism and is closely tied to the military-industrial complex. It thus has been complicit with the established order. AFL-CIO leadership has worked with the CIA throughout the post-Second World War era to repress progressive unions throughout the Global South, backing the most exploitative regimes. There is no doubt that in these and other respects, the upper stratum of labor (or its representatives) has opportunistically opposed the needs of both the majority of workers in the United States and the world proletarian movement as a whole. The labor leadership in Europe associated with social democratic parties has historically exhibited similar propensities. The overwhelming whiteness of the leadership of most unions in Western countries and the racism so apparent in them further helps explain reactionary support for imperialist policies by their governments.70

In the face of such historical contradictions, a new approach to imperialist denial on the left was introduced in Arrighi's Geometry of Imperialism (1978), which, despite its title, sought to use the concept of hegemony (part of imperialism theory) to displace the concept of imperialism as a whole, reducing it to its geopolitical aspects and avoiding the issue of international economic exploitation. For Arrighi, the old theories of imperialism, beginning with Lenin, were "obsolete." What remained was a world-system consisting of nation-states all jostling for hegemony. In The Long Twentieth Century (1994), Arrighi refrained altogether from referring to the term "imperialism" in relation to the post-Second World War world; while also abandoning the concept of monopoly capital via neoclassical transaction-cost theory.71

But it was the combined effects of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the subsequent wave of globalization, and Washington's aggressive drive for a unipolar order that led to much more open denials of imperialism on the left. Ironically, at a time when liberals were celebrating a new naked imperialism, much of the global left jettisoned all critical notions of imperialism theory, even, in some cases, offering support for the new empire ideology.72 Here the ideological hegemony exerted by capital over the Western left was on full display.73 In his "Whatever Happened to Imperialism?" in 1990, Prabhat Patnaik suggested that the "deafening silence" on the political economy of imperialism among European and U.S. Marxists in the 1980s and into the '90s, which constituted a sharp break with the '60s and '70s, was not the product of an extensive theoretical debate within Marxism. Rather, it could be attributed to "the very strengthening and consolidation of imperialism."74

An example of the retreat of the Western left on imperialism theory was Empire by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, published by Harvard University Press in 2000, and praised in all of the dominant media in the United States, including the New York Times, Time, and Foreign Affairs. Adopting an explicit flat-world perspective not entirely unlike that which was later promoted by New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman in his 2005 work, The World Is Flat, Hardt and Negri argued that the hierarchical imperialism of old had now been displaced by the "smooth space of the capitalist world market." It was "no longer possible," they pronounced, "to demarcate large geographical zones as center and periphery, North and South." In fact, "imperialism," they went so far as to assert, "actually creates a straitjacket for capital" by interfering with capitalism's flat-world propensities. Hardt and Negri were to give their notion of a rules-based, global-constitutional order, modeled on the United States, which was at the same time decentered and deterritorialized, the name "Empire," to distinguish it from imperialism.75

Hardt and Negri's work helped inspire Marxist geographer David Harvey's New Imperialism in 2003. Here, Harvey rerouted the theory of imperialism by way of Marx's concept of "original expropriation" (or "so-called primitive accumulation"), rebranding this "accumulation by dispossession."76 Expropriation, associated with robbery or dispossession, rather than the exploitation internal to the economic process, became the essence of the "new imperialism." The role of exploitation in Lenin's theory of imperialism, which linked it directly to monopoly capitalism, was sidelined in Harvey's analysis, leading to his fantasy of a "'New Deal' Imperialism" or renewed Good Neighbor Policy as the solution to international conflict. This view failed to see imperialism as dialectically connected to capitalism and as basic to that system as the search for profits itself.77

Although often characterized as a major theorist of imperialism, Harvey explicitly abandoned the core of the theory developed by Lenin, Mao, and the dependency, unequal exchange, and world-system theorists, classifying this entire almost century-long tradition as the outlook of the "traditional left." Instead, he presented his own perspective as akin to that of Hardt and Negri's Empire, which, he said, had posed "a decentered configuration of empire that had many new, postmodern qualities."78 To the extent that he still relied on the classical Marxist theory of imperialism, it was based on Rosa Luxemburg's notion of imperialism as the conquest and expropriation of noncapitalist sectors, particularly in external areas, thus providing new markets to support accumulation, which were then absorbed into the overall capitalist system. Imperialism, in this view, constituted a self-annihilating reality. Although the renewed emphasis on expropriation, in Harvey's analysis, was important, the introduction of it in such a way that it displaced the role of international exploitation was a backward step.79

In 2010, in his The Enigma of Capital, Harvey went further, arguing that an "unprecedented shift" had taken place that had "reversed the long-standing drain of wealth from east, south-east and south Asia to Europe and North America that has been occurring since the eighteenth century—a drain that Adam Smith noted with regret in The Wealth of Nations…. [This] has altered the center of gravity of capitalist development."<a id="en80backlink" class="endnote-link" href="https://monthlyreview.org/articles/the-new-denial-of-imperialism-

Najnovije vesti

-

20. Oct 2025.

The New Denial of Imperialism on the Left

AKTUELNO

Umetnička zadruga u izgradnji: Radionica #1, 6 - 9. jun, Beograd

Saopštenje povodom poziva studenata fakulteta Univerziteta umetnosti u Beogradu